Scanning For Names

There is a cluster of questions writers often face. The primary one, I would guess, is some version or another of “Did that really happen?” usually accompanied by, “I know someone just like that.” Then there are the other questions about where the ideas come from, the frequency of writing, how one might make a living as a writer. And of course there’s, “Would you be able to take a look at a few short pieces of mine for me?”

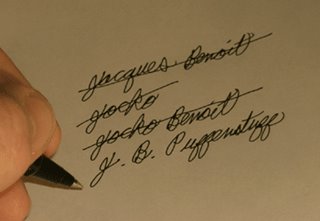

In my case, there has often been another question that I’ll admit I’ve brought on myself through a single decision I made a long time ago to not go by my given name, but by the name I grew up being called. The question is, “So why do you go by ‘Jocko’ instead of ‘Jacques’?” I wouldn’t bother anyone with my thoughts on this, but that question has been the most pressing one for people asking about my work and I’ve had to think about the reasons for this a good deal and so have decided to inflict those thoughts now on others.

So I’ll answer the question. In several stages.

My name began in the midst of a political struggle between my French grandmother and my English mother. When the baptismal bloodbath had cleared, the name of my baptismal certificate was: Joseph Pierre Alexandre Jacques Benoit. Joseph was a traditional name given to all Quebec-born boys, and the other tradition was to list the names in reverse. But for years my driver’s license said “Joseph Pierre Benoit”, my S.I.N. card said “Jacques Pierre Benoit” and all my other I.D. said “Jacques Peter Benoit.” This last complication was because my mother was under the impression I had received “Peter” after my grandfather rather than “Pierre” after my uncle. So for years I filled in forms as Jacques Peter Benoit. When we found out the truth, I kept the name Peter as a way of balancing out all the other French names. The French-English war over my name was hopefully, by then, over.

Shortly after I decided as a teenager that writing gave me more bang for very few bucks than any other activity I’d tried, my mother threw her support behind me (all the while emphasizing that I would have to have a real job as well – a rule she reminds me of probably only once a week now). She was pleased on returning from a convention one year to present me with a novel she had found. On the cover I could see the big, broad lettering: “Jacques Benoit.” A well known French writer of science fiction and fantasy. Since I was thinking about going into science fiction, this bothered me a little, but I consoled myself with the fact that he was solidly a French writer while my name only sounded like that of a French writer.

It was not long after this that I discovered “Jacques Benoit” was one of the most common names you could find in Quebec at the time. For that matter, my father’s name was Jacques Benoit. Technically I was a Jr., although no one has ever called me that. My father was someone I hadn’t seen since I was five and I began to wonder if I really wanted to write under that name.

There are, in Canada, other complications as well. For one thing, my name is French and I don’t speak French. And in the early 80’s with one referendum down and any number left to come, I wondered if it was a wise thing to be a French-named English speaker. For one thing, I was a French-born ex-Quebecois who had lost his grasp of the mother tongue. I was exactly the kind of child the French were afraid would proliferate. Let’s face it - I was the reason the province wanted to separate from Canada, although I tried not to take it personally.

With all these things in my mind when I first attended the poetry sweatshop at The Rivoli in Toronto, I was all set to write a poem that night in late 1987. I had watched a few of these events before and laughed now and then at the names people chose to go under. I wasn’t quite so adventurous and decided to write my first poem for the sweatshop as Jocko. It was the name my mother called me. It was what my father was called during his rowdy boarding school days. It was a name that sounded like a little bit of trouble. Exactly the kind of image I wanted for my poems, and it wasn’t even a name change at all. Besides, so many poets went by three names, I figured that going by just one name was my way of contributing to name conservation and maintaining the etymological balance. Over the next several months, I was a finalist in the competitions a few times, and even one of the winners once. My new writing name was off to a good start.

I began sending poems out under that name and after a few acceptances, the troubles started. Because I self-addressed my poems to “Jacques” (I didn’t want the mail getting lost) many editors began to ask to publish my poems under my ‘real’ name. And some editors simply insisted they couldn’t publish a one-name poet. Other editors simply published my work under my given name without even asking me about it. Two poets I approached after readings were very friendly until they asked me my name and then they gruffly insisted I use my given name. If I had used a pen name from the start, none of this would have happened. But there was something about my nickname that was getting me into trouble. Eventually, I started compromising by writing under “Jocko Benoit” and the publications in more ‘serious’ magazines picked up.

One of the most common things I heard was that I should use “Jacques Benoit” because “it’s such a nice French name.” No one ever said it was a nice name – always a nice French name. And I wondered if there were different standards for nice English names and nice French ones. And of course, these were all Anglos saying this to me. I began to pick up on the subtlest of prejudices underneath it all. Or it could have simply been that, as the restaurateur in the film Addicted To Love argues that his foreign name and accent in a country like America make him like Superman, maybe I was throwing away an obvious advantage.

At one point I looked up the two first names on a web name database and found that “Jacques” is often perceived as a stable, conscientious and accountant-like individual while “Jocko” is often more of a jester, a rambunctious ne’r-do-well. In many ways, the two names together probably aptly sum me up. But in my poetry I wanted to be the latter with just a hint of the former. My poetic voice works best when it is telling people all the wrong things to do, and when it is being petty and jabbering at the idiots (which would include everyone, I suspect). The tone of my poems has to be unpoetic wherever possible.

And that is probably the main sin of my name. It doesn’t sound like a poet’s name. It doesn’t convey the right tone or air. Never mind that it suits the image I want for my work. It doesn’t have the proper seriousness for the job. It’s the name of shipyard workers who open bottles (and possibly cans) with their teeth, or Aussies who sell batteries on the telly (well, actually, his name is Jacko), or the guy who shoulders you heavily as he walks out of the bar you’re going into and is obviously looking for a fight, the slick-looking guy in the suit who’s always coming onto your wife at work and the only way she can get him to move on is to let him surreptitiously cop a feel or two so he can know he got some. Meanwhile, my last name has the same root as “benediction” and “beneficence,” providing a neat balance that I hope my poems represent as often as possible.

Still, for many the image my nickname conveys is wrong. And we all know that when you’re trying to sleep with close relatives or cheat on your spouse (yes, I’m talking to you Byron-Coleridge-Poe-etc.), it really helps to have a Lord in front of your name or perhaps a good sturdy middle moniker or dignified initials that make everything scan nicely for the reviewers.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home